Apr 11, 2018

‘Extreme bacteria’ a game-changer for organic vegetable production

A Clemson University research scientist has obtained a patent for a way to make organic fertilizer that could revolutionize the organic produce industry and put it on a level playing field with conventional crops.

A Clemson University research scientist has obtained a patent for a way to make organic fertilizer that could revolutionize the organic produce industry and put it on a level playing field with conventional crops.

The limited potency, precision and consistency of organic fertilizers has long hindered organic vegetable production. But Brian Ward, an organic vegetable specialist at Clemson’s Coastal Research and Education Center, has developed a method for using “extreme bacteria” isolated from the stomachs of cattle to produce an organic fertilizer so rich with ammonium that it rivals synthetic fertilizers.

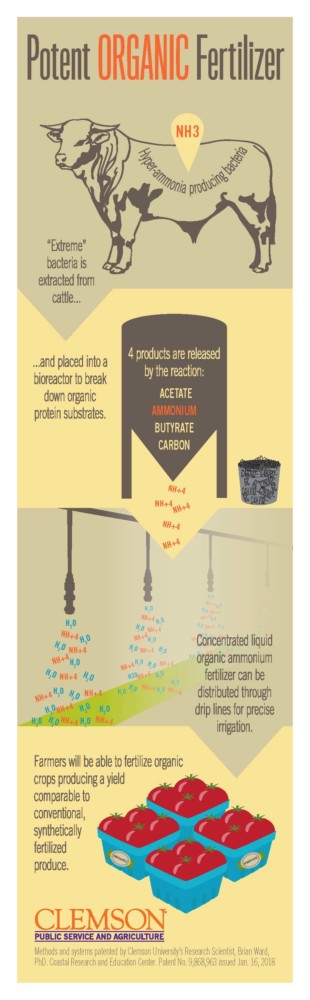

The hyper-ammonia-producing – or HAP – bacteria break down proteins that bind nitrogen to ammonia significantly faster than any other known bacteria, which allows ammonium nitrate to be produced in vast amounts at an accelerated rate.

“Ultimately, if we start to get the fertilizer commercialized, producers would be able to fertilize organic crops and have the yield comparable to conventional produce without the lag time of existing organic produce,” Ward said.

Making the process all the more innovative, unlike synthetic fertilizer, it does not require the use of fossil fuels, meaning it’s also an environmentally friendly technology.

“Two percent of the world’s energy is devoted to making ammonium fertilizer,” Ward said. “This does it organically, so there would be a huge cost savings.”

The patent itself describes methods for producing ammonia and ammonium in accordance with strict organic farming certification standards. Ward’s patent also describes specifications for creating a bioreactor for creating the chemical reaction needed to produce the super-potent organic fertilizer.

Organic fertilizer’s effectiveness depends on how active bacteria are in the soil. Ward’s process overcomes that obstacle through the use of the “extreme bacteria” to effectively activate the nitrogen in the soil.

With the patent for the process in place, Ward’s goal is to increase its output to a level between 1,000 to 10,000 liters.

“Once it’s proven on that level, then it’s feasible to go to 100,000 liters,” he said. “And once you have it at 100,000 liters, then it’s on a mass-production level.”

At that point, the process would produce a liquid fertilizer that could be fed through drip lines for irrigation for more precise use of a completely organic fertilizer comparable to synthetic ammonium.

Clemson professor and Extension vegetable specialist Richard Hassell agreed Ward’s process has the capacity to revolutionize the organic produce industry by providing growers with an unprecedented level of consistency in an organic fertilizer.

Most people have likely seen traditional synthetic fertilizers in home and garden stores labeled with three numbers on the bag to represent the primary nutrients — nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). For example, a bag of 10-10-10 fertilizer contains 10 percent nitrogen, 10 percent phosphate and 10 percent potash.

“With Brian’s process, he can produce an organic, liquid fertilizer with the same consistency, in the same ratios, in that product,” Hassell said. “It’s very concentrated, and he can produce the exact same amount of the nutrients involved every time.”

For Hassell, who directs vegetable research at the Coastal REC, Ward’s patent epitomizes the center’s mission and is a feather in the cap for Clemson University’s research efforts.

“Brian is a very determined scientist, and he set out to come up with this and tried all kinds of things, and like with all scientists, stumbled on to this through many, many tests and many trials and was able to come up with process, which is an amazing thing,” Hassell said.

While the potential of the patent could revolutionize the organic produce industry, it was a long time in the making. Specializing in organic vegetable research at the Coastal REC, Ward was challenged by a mentor to prove organic production was healthier, cleaner and capable of comparable production to conventional agriculture.

“I said, ‘I can’t do it because the fertilizers you use are like comparing apples and oranges,’” he said. “One can readily absorb nitrogen in the soil, and the other takes time and the soil for it to happen.”

But undeterred, Ward’s research led him to identify the HAP bacteria, and a network of colleagues eventually led him to a U.S. Department of Agriculture research facility at Texas A&M University, hoping to obtain a pure culture of the HAP bacteria from a cow’s stomach.

“I eventually brought them back to my lab and ultimately was able to get the bacteria growing and maximize their ability to make ammonium,” he said.

Ward engineered a bioreactor in his lab at the Coastal REC and used it to create a reaction that releases four products: ammonium, butyrate, acetate and nearly pure carbon, similar to coal.

He was able to use the ammonium released to produce a liquid fertilizer that could be fed through drip lines as a precision organic fertilizer.

But working out the science was just the first step toward getting the patent. Ward contacted the Clemson University Research Foundation in 2006 about its Technology Transfer program, which refers to the process of moving technology out of the laboratory and into commercial markets.

CURF applied for the patent on Ward’s behalf in 2006, but the innovation had to overcome a series of legal hurdles, most notably meeting the United States Patent and Trademark Office’s conditions for patentability in regard to the nonobvious subject matter.

After a decade-long fight, Ward finally got the word last fall the patent could move forward.

“That was such an awesome feeling after 11 years of battling, but I never gave up hope,” he said. “The Clemson University Research Foundation supported me for 11 years with the legal issues in obtaining this patent. They had faith in the potential technology and so that’s why they supported me through the fees that it took to patent it.”