Nov 2, 2022

SWD-killing wasps released to protect Michigan fruit

Michigan State University (MSU) researchers who specialize in fruit crop pests have begun testing the effectiveness of a new biocontrol agent that could help reduce the damage caused by spotted-wing drosophila (SWD) on crops.

This invasive pest has been one of the top production challenges for berry and cherry growers in recent years since it arrived in the United States. The samba wasp (Ganaspis brasiliensis) is a tiny parasitic wasp that lays its eggs in SWD larvae.

After years of evaluation and permit review, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (through its Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) and the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development have approved release of this wasp in regions where it threatens fruit production.

One of the MSU researchers, Juan Huang, traveled in April to the USDA lab in Delaware and received training on the rearing process. She returned to MSU with 100 of these insects to begin mass-rearing efforts. Sufficient numbers of wasps are now in colony, with releases having taken place recently for cherries at the Northwest Michigan Horticulture Research Center in Traverse City, Michigan, and on Aug. 18 for blueberries at the Southwest Michigan Research and Extension Center (SWMREC) in Benton Harbor.

The researchers will assess the impact of this new species on SWD populations and their potential for establishment in Michigan’s climate. This program provides hope for improved integrated pest management practices on fruit farms across Michigan and the potential to reduce their potential for establishment in Michigan’s climate. This program provides hope for improved integrated pest management practices on fruit farms across Michigan and the potential to reduce insecticide spraying for this pest.

“This tiny little wasp is flying around looking for berries that are infested already with spotted-wing drosophila larvae,” said MSU entomologist Rufus Isaacs.

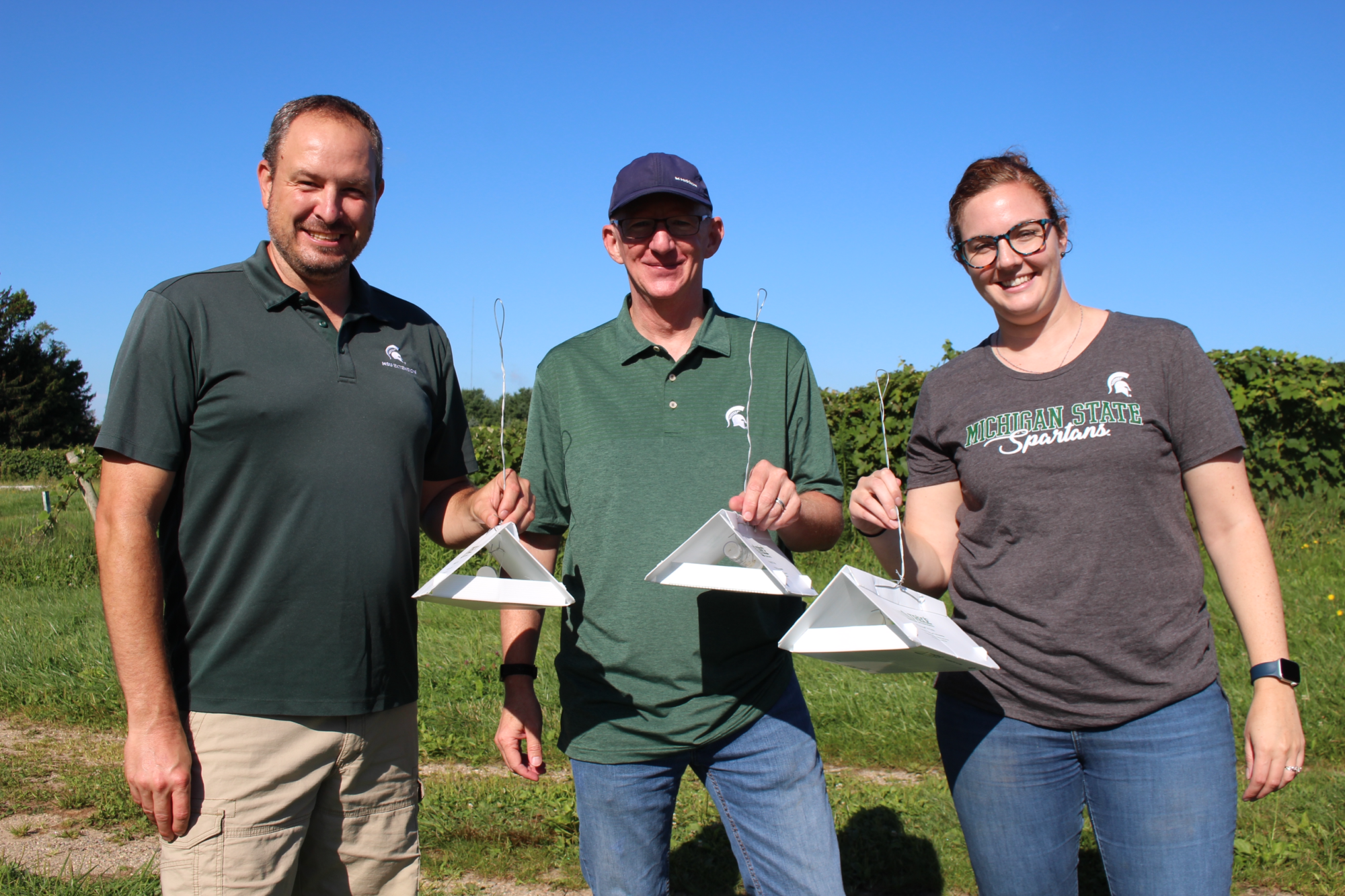

Isaacs, lab manager Jackie Perkins, and Integrated Pest Management Educator for fruits and vegetables for southwest Michigan growers, Michael Reinke, released three vials of the samba wasps in a SWMREC test plot of Elliott blueberries on Aug. 18.

“A lot of that will be in wild habitat around the farms,” Isaacs said. “Their job is to find a blueberry that’s infested with SWD larvae. They will stick their egg layer into the berry, which contacts the inside of the SWD larvae, and they will then lay their egg into the fruit, inside the spotted-wing drosophila larvae. And then it develops on the inside, killing that larvae, and comes out as a wasp in about a month.”

Issacs said the wasps are then going to mate. Each wasp should lay approximately 60-80 eggs.

“We’ve already been monitoring the percentage of native wasps in this field this summer,” he said. “Now, we’ve done these releases and will be coming back here to see if we can recapture this emerging out of the spotted-wing drosophila population here and in the other sites we’re doing the releases for.”

It took years of evaluating many kinds of wasps to see which one would deliver the best results.

“This one was selected and then went through jumping through the hoops that you have to do to get the testing done, including approvals from USDA-APHIS,” Isaacs said.

“There is already detection of this wasp species in Washington state, so they’re a little bit ahead of us. By doing this we are hoping everyone can catch up.”

The MSU researchers are releasing the wasps in Trécé Inc. SWD traps, which provide a dispersal point for the wasps to move into the blueberry bushes.

The traps hang in the bush part of the plant, placed far enough in so that workers don’t knock them off when coming through with equipment.

When Reinke pulled the plug on the first vial of wasps, an SWD fly conveniently landed on the trap, providing a proof of concept-type realization.

“We can be a little ceremonial with it,” Perkins said. “The process for rearing these is quite complicated. You have to have fresh fruit. You have to have a colony of (SWD) flies to access that fruit. You have to transfer wasps using an aspirator-type device. Each individual wasp to get sucked up with an aspirator and transferred on to that infested fruit. You leave them on the fruit for 5-7 days. Once they’ve laid eggs into that larvae, you transfer them on to the next stage of infested fruit.”

MSU student Andrew Jones has been handling most of that process, and the specific conditions, such as humidity, has been a learning process for everyone in the project.

“It’s the end of a long journey to get here, but it’s also just the start of being able to see how they work,” Isaacs said.

A national effort

Collaborating researchers recently released the wasps in selected West Coast locations hoping they’ll establish and help control the SWD.

“In Michigan, we’re doing it here and in Traverse City with cherries and other researchers all across the U.S. are doing trials in other states and other settings,” Isaacs said. “That group of entomologists across the country will be comparing notes and seeing where it establishes well and where does it reduce SWD populations. That will take years to measure the long-term benefits of the (wasps).”

The wasps are being released at some unmanaged sites where they won’t be sprayed, to give them a better chance to establish a population. Releases at commercial sites could start in the fall, Isaacs said.

He acknowledged it will be a long process to bring the wasps to growers on a regular basis.

“We’re still trying to improve the rearing methods to make it easier than it currently is,” he said. “In farms, the release will be more likely in the woods and wild habitat where you’ve got this reservoir of spotted-wing drosophila coming into the farms, partly because growers are spraying to protect the fruit from spotted wing drosophila and these (wasps) are very sensitive to pesticides.

“At the moment we’re thinking maybe an early season release that you might do to kick-start biocontrol for this pest in the spring,” he said. “Then releases would be going on through the summer, primarily in the wild areas to try to reduce the invasion that you keep getting from the edge of the fields.

While there are commercial insectaries that raise biocontrol agents, Isaacs said, it’s undetermined whether a commercial distributor will supply the program.

Widespread application

The samba wasp will go on any fruit host where spotted-wing drosophila exist. As the pests move to different hosts over time, “the wasps will hopefully follow those,” Isaacs said.

“It’s a very active area of research. Some labs are already planning and overwintering study of these wasps. We will see how well they survive the Michigan winter.

“We have good habitat on the west side of the state,” Reinke said. “We have good snow cover that will protect them over the winter.

Isaacs said the original funding for much of the discovery work came from Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI) funding to California, Oregon and Washington.

“We’ve had more recent SCRI grants that have helped us continue the biocontrol evaluation and all of the work that had to be done to get to the point of having an approval for release,” he said.

The Michigan Department of Agriculture is funding the program through a specialty crop block grant, as well as the Michigan Blueberry Commission. Project GREEEN funding is paying for the work to ramp up the wasp population.

PHOTO: From left, Michael Reinke, Michigan State University (MSU) integrated pest management educator for fruits and vegetables for southwest Michigan growers; MSU entomologist Rufus Isaacs and lab manager Jackie Perkins prepare to release samba wasps in a test plot of blueberries on Aug. 18.