May 9, 2022

Matching soil nutrients to crop demand

We can say that growing organic requires more nuance than chemical methods. Nowhere is this more true than in assuring the presence and availability of nutrients to our crop. Chemical growers can apply fertilizers that are both potent and water-soluble. And because synthetic fertilizers dissolve in water they are more quickly available to the plant (because plants drink their food).

In contrast, organic fertilizers are generally less concentrated – a typical synthetic fertilizer analysis might be 20-20-20 (20% nitrogen by weight) whereas an organic poultry litter fertilizer may be 4-3-3.

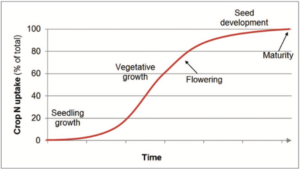

In addition, the nutrients in organic fertilizers are generally less water soluble and slower to release, instead, soil microbes must break down the nutrients to make them available to the plant. What is the same is that the plant’s demand for nutrients changes throughout its lifespan. As annual plants mature, the amount of nutrients they require at first is low but then increases quickly with rapid growth. This is called a nutrient demand curve (see Figure 1).

We don’t want all of the soil’s nutrients available when the plant is young, or already mature, but rather the bulk of nutrients are most needed during rapid uptake in the middle of the season. How do we match the soil’s supply to the plant’s needs?

For insight on such a question I turned to a friend at Michigan State University, professor Zack Hayden in the department of horticulture. Hayden studies nutrients and soils in vegetable crops.

Hayden began by telling me that there are other crucial elements of soil care that have to be in place first before considering matching nutrient release from the soil to crop demand.

“There is so much complexity out there, and a mystery to the soil – a lot of what I’ve tried to do for growers is simplify. There are some key things that growers need to understand with organic nutrients and timing to crop demand.”

Hayden described soil care as a pyramid, constructed with the most important elements at the bottom. The most important part of soil a grower must get right is moisture. Plants drink their food and soil biology, like us, needs water to function. Solve any drainage or irrigation issues first before worrying about the hottest new kelp- humic-trace-mineral-molasses blend.

Next is pH, or the concentration of hydrogen ions in the soil. Even if your soil is teeming with fertility, the wrong pH can make nutrients unavailable to your plants or can make them present in toxic amounts. Take a pH test every three years. After we’ve got water and pH under control, we should think about our macro nutrients – those that the plant needs in greatest amounts. These are nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (N-P-K). Of these, nitrogen is our chief concern. This is because phosphorus and potassium aren’t lost from the soil as quickly, whereas nitrogen is very soil-mobile, which is to say it can be lost either through a big rain that leaches it out of the soil profile or as those pesky microbes suck it up for themselves to process carbonaceous material.

After dialing in macro nutrients a grower should focus on their micro nutrients.

“Often your soil test will tell you if any micros are in particularly short supply, but if you’ve been using organic fertilizers like compost or manure, these may already add enough micro nutrients,” Hayden said.

And finally at the tip of that pyramid are biologicals and specialty products, like mycorrhizal fungi or kelp extract, for example.

“You’re welcome to try them, and sometimes they might give you an edge – but don’t look at these until you’ve got all the other areas addressed,” Hayden said.

After attending to the basics of soil fertility we’re ready to talk crop nutrient demand, and when we do, we’re usually referring to nitrogen, since it is needed in largest amount and is easily lost from the soil. Because the other nutrients are better held in the soil a soil test can guide us on the levels to apply for phosphorous, potassium, etc. But because nitrogen is so mobile the recommendation is to assume you need to apply all that the crop will need each season (and this is also why nitrogen is not typically part of a standard soil test).

Look at your university’s conventional N rates for your crop – because as Hayden puts it, “the plant needs what it needs regardless of where it comes from.”

Row crop growers should have plenty of localized resources. Vegetable growers lacking local university research can look at Nutrient Recommendations for Vegetable Crops in Michigan. These overall, season- long rates are relatively simple to look up and apply.

Now here’s the rub with organic nitrogen fertilizer. It is not all available to the plant in the first season, because the microbes have to break it down.

Hayden gives the following rule of thumb, “if the fertilizer is above 4% N, assume half of the nitrogen will be available the first season, and most of that nitrogen will be plant-available in the first 2-4 weeks after application. However, that timeframe depends greatly on weather and soil conditions hospitable to microbes so that they can break that fertilizer down and make it plant-available.

“If you’ve got colder or drier or too wet then the microbes won’t work as fast, or you can lose N already made available,” he said.

Because the nutrients in organic fertilizers are made available to plants through microbes, incorporating them into a soil with proper moisture makes more of those nutrients plant-available sooner.

But what about the other half of that N – we’re assuming that only half of our applied N is available the first season – in seasons following the application of that fertilizer? Can I count some of that slow-releasing N toward my total nitrogen rate for that season?

“You can and absolutely should give yourself an N credit for the work you’ve done on your soils in the past – the problem is that it’s so hard to know how much N will be available in subsequent years after an organic fertilizer is added, it’s hard to get right,” Hayden said.

Recently, more concentrated and highly soluble organic N fertilizers have become available, many having between 12-16% N. In Hayden’s experience, these materials work like you’d expect based on their description – a greater percentage of the total N will become available in the first season (say 75%), and perhaps more quickly, than with lower N organic fertilizers.

For longer-season crops where you are worried about running out of fertility, side dressing is helpful. The necessary side-dress rates can again be borrowed from fertility management resources not specific to organic growers. You will just apply it using an organic source, and account for slower and less complete N availability. For example, for hard squash the recommendation is to incorporate 30-40% of the total N needed at planting and the remaining balance in the middle of the season. For organic side dressing, apply the N a week earlier than the conventional timing to give the microbes some time to make it available.

This all sounded like doable agronomic advice. I asked Hayden about how to keep up with new soil research and he replied, “Nutrients are different from herbicide recommendations or pesticide recommendations (where diseases evolve and approved products change each year) – not a lot of the basics for nutrient management have changed in the last 20 years. In 20 years, the basics of what the crop needs and when have remained pretty consistent.”