Mar 11, 2020

Grower research priorities for North Central region organic apple production

Demand for organic apples has steadily increased over the past two decades. That includes double-digit increases in annual sales the past decade – as high as 40%.

Market expansion, including both fresh and processing apples, is in sharp contrast to trends in the commercial apple marketplace, which has seen major decline in processing prices over the same period. This is similar to the general trend for organic crops and products across a wide swath of agronomic, specialty and animal agricultural industries and has sparked the interest of a diverse group of farmers, especially those looking to remain sustainable in the face of an increasingly consolidated food system. Simply put, the economic premium afforded by organic certification can provide growers with a niche market, allowing them increased margins and, for some, an alternative to the “get big or get out” economic model that has come to characterize U.S. agriculture over the past 70 years.

Photo: Gary Pullano

Two natural questions that emerge from this are:

- Why do so few organic apples come from outside

of Washington? - How can growers outside of Washington enter

this market space?

These questions were the centerpiece of a recent panel discussion at the 2019 Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable & Farm Market in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Panelists included both experienced and new organic growers including: Jim Koan (AlMar Orchards), Steve Tennes (The Country Mill), Mike Adsit (Plymouth Orchards) and Gunnar Nyblad (Grizzly Organics).

During the session, the panelists provided an overview of their experience in organic apple production and talked about some of the challenges they had overcome in the development of their orchards as well as the challenges they are still facing.

A common narrative from all the growers was that input substitution (trading conventional pesticides and fertilizers for certified organic products) was not a successful strategy in the temperate climate of the North Central region.

Another common theme was how each of the experienced growers had worked to carefully develop markets for their apples, especially the 40%-plus that would not make the grade in a packing house. The approach common to these established orchards was to develop onsite value-added products – largely fresh and hard cider – from seconds. Additionally, all of the established orchards relied to some extent on agritourism to help supplement farm income with one farm marketing both organic and conventionally produced apples and other fruits.

Following the introduction, the audience was encouraged to ask questions and a list of actionable challenges developed from the discussion that ensued.

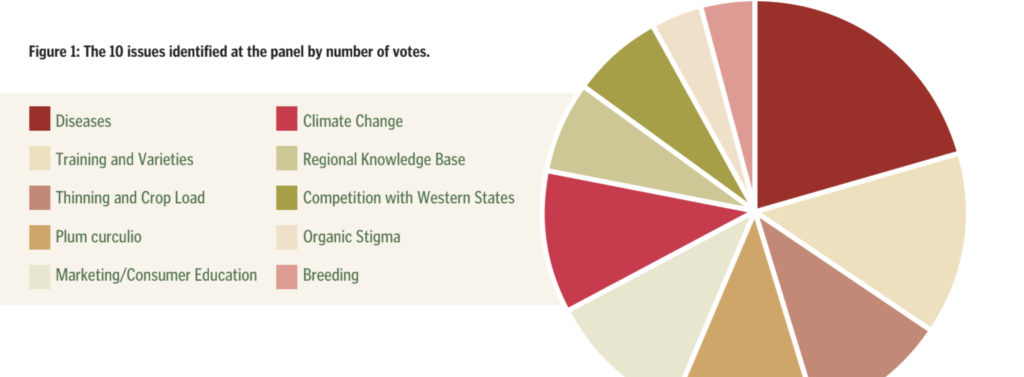

Challenges identified by the panel and the audience ranged from production to marketing and consumer education. Following the development of a list of challenges the audience, including panelists, were asked to prioritize the challenges by placing four tags/participant on the challenges they felt were most important. (The full range of issues is presented in Figure 1.)

The broad consensus of the participants was that the biggest challenges were largely production-oriented with production issues making up six out of the 10 identified priorities and claiming two-thirds of the total votes.

The most important production issues ranged from the management of diseases and pests (especially apple scab and plum curculio), the selection and training of organic appropriate scion and rootstock combinations and thinning and crop load management. Not surprisingly, the impact of a changing climate on apple production was also an identified priority. Marketing/consumer education was identified as the No. 1 non-production issue with an emphasis on educating consumers on the palatability/merits of organic and regionally specific varieties (e.g., scab resistant varieties) as well as the “Terroir” of regionally produced apples.

Other issues included how to compete with Western production, especially in retail outlets, the development of a regional knowledge base for what works in organic apple production, the development of a regionally appropriate breeding program as well as how to address the organic stigma some growers felt in communities with a long history of conventional production.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the session was the organic growers’ (panelists and audience both) willingness to share what has worked and hasn’t worked on their farms.

One grower reported on his success managing plum curculio through mass trapping (using 15-20 traps per acre). Another shared their experience using biological inputs designed to break down corn stover to speed the decay of leaves carrying next year’s scab inoculum. Growers shared experiences with multi-leader systems, including which rootstocks seemed best suited to this approach (B9 and M9 proved too low vigor).

Yet another shared their experience marketing “weather-kissed fruit” in their local farm market. Two growers even shared tips on flame weeding techniques for asparagus, of all things.

Building organic apple production in the North Central and Eastern regions will no doubt be challenging, but with the rapidly changing marketplace it may provide some growers with the ability to maintain sustainable farm income on smaller acreage.

However, competing with Washington production at the national scale seems unlikely, making the education of regional consumers on the merits of locally produced apples of paramount importance.

It is clear that rising to this challenge, as well as developing organic production practices appropriate to the more humid climate of these regions, is beyond the capacity of a single farm or state. The most likely way forward is for regional growers and commodity groups to work together. Such a model would most likely be successful if areas of common interests between conventional and organic grower can be identified.

Building a community that cuts across the conventional/organic divide where individual growers feel comfortable to share their successes and failures would be a great first step in this direction.

Above, Organic Golden Delicious apples picked in Washington. Photo: Stephen Kloosterman